Abstract

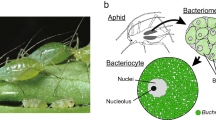

Almost all aphid species (Homoptera, Insecta) have 60–80 huge cells called bacteriocytes, within which are round-shaped bacteria that are designated Buchnera1. These bacteria are maternally transmitted to eggs and embryos through host generations, and the mutualism between the host and the bacteria is so obligate that neither can reproduce independently2. Buchnera is a close relative of Escherichia coli3, but it contains more than 100 genomic copies per cell4, and its genome size is only a seventh of that of E. coli5. Here we report the complete genome sequence of Buchnera sp. strain APS, which is composed of one 640,681-base-pair chromosome and two small plasmids. There are genes for the biosyntheses of amino acids essential for the hosts in the genome, but those for non-essential amino acids are missing, indicating complementarity and syntrophy between the host and the symbiont. In addition, Buchnera lacks genes for the biosynthesis of cell-surface components, including lipopolysaccharides and phospholipids, regulator genes and genes involved in defence of the cell. These results indicate that Buchnera is completely symbiotic and viable only in its limited niche, the bacteriocyte.

Similar content being viewed by others

Main

One of the principal ecological niches of microbes is the inside of eukaryotic cells6. Although the majority of associations between microbe and eukaryote is either commensal or, quite often, mutually beneficial, most studies of animal-associated microbes have dealt with those rare bacterial species that cause diseases. Our major interest focuses on endocellular mutualistic bacteria, which, unlike pathogenic parasites, have been transmitted through host generations for an evolutionary length of time. The endocellular mutualistic associations must have evolved repeatedly and have had major consequences for the diversification of both bacteria and hosts. One typical mutualism is observed in the symbiosis between Buchnera and aphids. A phylogenetic analysis has indicated that the symbiotic relationship was established 200–250 Myr ago and led to co-speciation of the hosts and their symbionts7.

Buchnera sp. APS is harboured by the pea aphid, Acyrthosiphon pisum (Harris). We sequenced the Buchnera genome by the whole genome random sequencing method. The genome comprises one circular chromosome and two circular plasmids, pLeu and pTrp. The chromosome is 640,681 base pairs (bp), the smallest of the completely sequenced genomes, except for that of Mycoplasma genitalium (580,070 bp) which is regarded as a genome of the minimal gene set8. The pLeu plasmid is 7,786 bp and has 7 open reading frames (ORFs) including a leuABCD operon, and the pTrp plasmid has at least two tandem repeats of the trpEG operon3,9,10. The average G+C content of the Buchnera genome is 26.3%. This AT richness is a feature of many endocellular bacteria, including both endosymbiotic and parasitic bacteria11.

As E. coli and Haemophilus influenzae are closely related to Buchnera phylogenetically (see below), we assumed the DnaA box upstream of the gidA gene is the replication origin, and designated the start of the DnaA box as base pair one. Buchnera has only one DnaA box, and slight shifts in the GC skew values are observed at the third codon position and in the non-coding region around rho, which is located 13 kilobases (kb) upstream of gidA (data not shown). We did not find an insertion sequence (IS) or a phage-related sequence by database homology search. Neither are there any significant repetitive elements. Buchnera has a single copy of each of the three types of ribosomal RNA and 32 transfer RNA genes.

We identified 583 ORFs in the genome with an average size of 988 bp, covering 88% of the whole genome (Fig. 1). It is intriguing that the predicted isoelectric points (pIs) of the products of the ORFs are on average much more basic than those of polypeptides of other bacteria. The average pI of Buchnera polypeptides is 9.6, whereas that of E. coli and H. influenzae polypeptides is 7.2 and 7.3, respectively. Comparison of amino-acid composition between E. coli and Buchnera shows that lysine usage of Buchnera is twice that of E. coli, causing the increased pI (data not shown). The 583 predicted ORFs were compared against a non-redundant protein database and their biological roles were assigned (Table 1). Similarity searching permitted the functional assignment of 500 ORFs, and another 79 ORFs are similar to hypothetical proteins deposited for other bacteria. Only four ORFs are unique to Buchnera. Generally, the most similar counterparts of Buchnera proteins are those of E. coli, and the gene order in E. coli operons is well conserved in Buchnera. Considering these observations, we conclude the Buchnera genome is a subset of the E. coli genome.

APS genome illustrating the location of each predicted protein-coding region and RNA genes. All of these are essentially circular. a, Chromosome. b, pLeu plasmid. c, pTrp plasmid. The trpEG plasmid is composed of tandem repeats of the trpEG operon. As the repeats are highly similar, the assembled sequence converged at 7,258 bp, which is equivalent to two units of the repeat. The pTrp plasmid of Buchnera of A. pisum may contain five, six or ten repeats of this operon3.

The biosynthesis capabilities of Buchnera characterize it as a symbiont. Endocellular and epicellular parasites that have dramatically reduced their genome size, like Buchnera, depend on their hosts for most nutrients, and the reduction of their genome size is, at least partly, due to the loss of biosynthetic genes for nutrients. However, nutritional and physiological studies show that Buchnera is a provider, rather than a recipient, of biosynthetic products including essential amino acids and vitamins, to its host3,10,12,13,14. We found 55 genes involved in amino-acid biosynthesis in the Buchnera genome. One of the most characteristic features of Buchnera, unveiled by our genome analysis, is that the genes for biosyntheses of the amino acids essential for the aphid hosts3,15 are present, but those for the non-essential amino acids are almost completely missing (Fig. 2). This complementarity of the gene repertoire shows how successfully the symbiosis is operating, in that Buchnera provides the host with what the host cannot synthesize, and conversely, the host provides the symbiont with what Buchnera cannot synthesize. Moreover, as the precursors of some essential amino acids are non-essential amino acids, glutamate and aspartate (Fig. 2a ), the biosynthetic pathways of both the host and the symbiont are not only complementary, but also mutually dependent. This analysis is consistent with experimental evidence that aphids do not usually excrete a nitrogenous waste product, but recycle the amino groups as glutamine, which Buchnera uses as a substrate for the synthesis of essential amino acids10,13,16.

The sequential pathways are represented by arrows, each of which indicates one step catalysed by the named enzyme. The steps for which no genes were found in the Buchnera genome are pink, as are precursors for which de novo synthetic pathways were not identified. a, Essential amino acids of animals. In the valine, isoleucine and leucine biosynthetic pathways, the gene for common enzyme ilvE is absent (purple). IlvE is a branched-chain amino-acid aminotransferase and typically the final enzyme in the pathway, so the reaction may take place by some other aminotransferase enzyme. In the lysine biosynthetic pathway, the dapC gene (blue) has never been identified in any organisms. The terminal step of the phenylalanine biosynthesis is catalysed by TyrB in E. coli, but HisC may substitute for TyrB in Buchnera . b, Non-essential amino acids of animals. The alanine biosynthetic pathway has not been elucidated, even in E. coli.

A similar example is observed in the pantothenate–coenzyme A (CoA) biosynthetic pathway. Although pantothenate seems to be synthesized from pyruvate in Buchnera, no genes for the pathway from pantothenate to CoA are found. On the other hand, animals generally have the ability to produce CoA from pantothenate, whereas they are not able to synthesize pantothenate itself. That Buchnera possesses complete gene sets for the sulphur reduction pathway and biosynthesis of cysteine is interesting, because insects cannot reduce sulphate to sulphide. Also experimental evidence shows that the Buchnera–bacteriocyte system is responsible for sulphate assimilation17. In contrast to obligatory parasitic bacteria, Buchnera has almost complete nucleotide biosynthetic pathways (Fig. 3). It is not known whether they are for the host or for its own use.

Pathways or steps for which no enzymes were identified are pink, as are the compounds for which de novo synthetic pathways were not identified. Question marks indicate that particular uncertainties exist or that the pathway has not been completely elucidated, even in E. coli. AICAR, 5′-phosphoribosyl-4-carboxamide-5-aminoimidazole; cAMP, cyclic AMP; DHF, dihydrofolate; GlcNac, N-acetylglucosamine; IGP, imidazoleglycerol phosphate; IMP, inosine monophosphate; PE, phosphatidyl ethanolamine; PEP, phosphoenolpyruvate; PG, phosphotidyl glycerol; PRPP, phosphoribosyl-pyrophosphate; PTS, phosphoenolpyruvate:carbohydrate phosphotransferase system; TCA, tricarboxylic acid; THF, tetrahydrofolate; UQ, ubiquinone.

Such an obligatory mutualistic association as that between Buchnera and aphids should be maintained through exchange of various substances between the symbiont and the cytoplasm of the host cell. However, only a few transporter genes are present in the Buchnera genome ( Table 1). Although the ABC transport system is a major class of cellular translocation machinery and many paralogueous genes involved in this system are found in all bacterial species sequenced to date18, Buchnera has only a few ABC transporter genes. Phosphoenolpyruvate–carbohydrate phosphotransferase systems (PTSs) seem to function in the Buchnera cell to import glucose and mannitol. Apart from these transporters, we found no other substrate-specific transporter genes. Hypothetical proteins YnfM and YajR are probably low-affinity transporters such as multidrug-efflux proteins. GlpF and OmpF-like porin may be involved in passive diffusion. The genes responsible for the sec protein secretion system are conserved in the Buchnera genome. Possibly, the flagellum of Buchnera serves as a transporter structure rather than a motor apparatus, as in Salmonella typhimurium and Yersinia enterocolitica19,20. In general, the flagellum is composed of three components: a basal body, a hook and a filament. In the Buchnera genome, however, there is no evidence for a gene for filament (fliC), which confers motility on the cell. In addition, Buchnera lacks genes involved in chemotaxis. Indeed, neither flagellum nor motility has been observed with Buchnera.

The genome data indicates that Buchnera respires aerobically. This seems reasonable as this bacterium inhabits the bacteriocyte, which receives an ample supply of oxygen through the trachea and contains many mitochondria in the cytoplasm. Buchnera has complete gene sets responsible for glycolysis, the pentose phosphate cycle and aerobic respiration; however, it does not have a gene set for operation of the TCA cycle apart from genes for the 2-oxoglutarate dehydrogenase complex. In the Buchnera genome, the NADH dehydrogenase (nuo) operon and the cytochrome o (cyo) operon are conserved with the same gene arrangements as E. coli, but the ubiquinone biosynthetic pathway is not even found. Buchnera has an F0F1 type ATP synthase operon, indicating that this bacterium is able to produce ATP using the proton electrochemical gradient generated by the electron transport system. Buchnera lacks genes responsible for fermentation and anaerobic respiration.

Buchnera seems to have a limited capacity for DNA repair and recombination, and exhibits an unusual repertoire of genes in this category. It is striking that the recA gene is missing from the Buchnera genome, as RecA is the most crucial component for the homologous recombination reaction. Buchnera is the first organism found to have recBCD without recA, though some mollicutes species have truncated recA21. Similarly, in the uvr excision repair system, Buchnera lacks uvrABC, but retains mfd. The recA and uvrABC are retained in all sequenced eubacterial genomes22, except for Buchnera. This unique inventory of repair genes implies that the repair system and the recombination mechanism of this symbiotic bacterium are severely impaired. Alternatively, Buchnera uses these residual components differently from other organisms to provide the minimum requirement for its survival. The absence of a series of genes responsible for the SOS system, recA, lexA, umuCD and uvrABC, indicates that the Buchnera genome is vulnerable to DNA damage. Genes for DNA methylation and restriction are also missing, further evidence that Buchnera has limited defences.

Buchnera has only a few genes for cell-surface components. Our genome analysis indicates that Buchnera is not able to make lipopolysaccharides (LPSs). The genes for the biosynthesis of the LPS components, except for lpcA and kdtB, are missing from the Buchnera genome. We found only a few genes encoding lipoproteins and outer membrane proteins. Scarcity of genes for these components indicates that the cell surface of Buchnera is structurally vulnerable. This is in contrast to other bacteria, including pathogenic and free-living ones, which have complex and flexible surface structures to evade attack by the host immune system or to survive harsh environments. This structural fragility of Buchnera may be caused by its prolonged intracellular life, sheltered from attack by the host and foreign enemies.

Surprisingly, genes responsible for phospholipid biosynthesis are completely missing from the Buchnera genome, except that for cardiolipin synthetase (cls), although phospholipid is an indispensable component in the formation of the membrane lipid bilayer. Possibly, Buchnera either imports phospholipid from the host or synthesizes it, employing relevant enzymes transferred from the host cell, like mitochondria do.

Another prominent feature of the Buchnera genome is that genes for various regulatory systems are almost completely missing. Among these are two-component regulatory systems, which generally control gene expression in response to environmental changes. In addition, all the other types of transcriptional regulators, except dnaA, are missing. Indeed, no transcriptional regulator of amino-acid biosynthesis is present despite the conservation of many genes for amino-acid biosynthesis. Comparison of operon structure between E. coli and Buchnera indicates that genes of Buchnera do not have leader sequences, and that Buchnera is not equipped with a transcriptional attenuation system. Although Buchnera has PTSs, which are involved in catabolite repression through cyclic AMP in many bacteria, the genes for adenylate cyclase (cyaA) and cAMP receptor protein ( crp) are absent, indicating the lack of transcriptional regulation for the response to carbon-source change. Instead, a carbon storage regulator CsrA might be involved in global post-trancriptional regulation of the carbohydrate metabolism23 in Buchnera. The Buchnera genome contains only two predicted sigma factors, rpoD and rpoH. Other parasitic bacteria with small genomes, such as M. genitalium and Rickettsia prowazekii, have also lost large parts of their regulatory systems. However these organisms have also lost the genes that are normally under the control of the regulators. Buchnera is unique in lacking regulatory genes, but having their regulatees. It is possible that the loss of regulatory genes is a consequence of the homeostatic environment in which Buchnera has been housed for so long.

To evaluate the evolution of the characteristic gene set in Buchnera , we tried to reconstruct the history of Buchnera. First, we determined the evolutionary position of Buchnera among prokaryotes. We made orthologue groups of all ORFs in 23 complete prokaryotic genomes. For each group, we constructed a molecular phylogenetic tree and inferred the most plausible phylogeny of Buchnera and its relatives by searching for the most frequent sub-tree of the same topology that included one or more Buchnera genes or domains. The results indicate that after the speciation of R. prowazekii , Buchnera then diverged from the lineage to E. coli and H. influenzae, although a certain number of trees support the topology in which the closest relative of E. coli is Buchnera. To see whether the Buchnera genome is small because the genome of the last common ancestor (LCA) of Buchnera, E. coli and H. influenzae was as small as that of Buchnera, or because of gene loss in Buchnera after speciation, we inferred the gene set of the LCA. The gene set of Buchnera, excluding a few genes, is a small subset of that of the LCA, and many genes of the LCA were missing in Buchnera, such as those for non-essential amino-acid metabolism. In addition, no Buchnera -specific duplicated gene was found. These results strongly indicate that the small Buchnera genome is the result of reductive evolution.

The gene repertoire of the Buchnera genome is so specialized to intracellular life that it cannot survive outside the eukaryotic cell. Although the features of genome size reduction and heavy reliance on the host are shared between obligatory parasites and Buchnera, the gene sets show a marked difference in the manner of dependency between these two types of organisms. Whereas parasites depend upon nutrients from the host commensally, Buchnera provides nutrients to the host, using host-derived precursors. Moreover, Buchnera even seems to owe its membrane bilayer to the host and requires the host's protective environment. In this view, Buchnera is similar to organelles, which also require the endocellular environment of the host cells and make a contribution to the host, for example, in energy production.

This study is the first case where genomic evolution of a mutualistic organism is revealed at the genomic level. Although this kind of organism has been difficult to study experimentally because of its absolute mutualism, this genomic data should promote experimental approaches to symbiosis, and further experimental data may give us an even deeper insight into the evolutionary significance of tight interspecies associations.

Methods

Whole genome random shotgun sequencing

We prepared genomic DNA from the APS strain of Buchnera sp. harboured by the pea aphid, Acyrthosiphon pisum (Harris). A. pisum is a long-established parthenogenetic clone maintained on young broad bean plants, Vicia faba (L.), at 15 °C under a long-day regime of 18 h light and 6 h dark. We collected the bacteriocytes by dissecting 2,000 pea aphids in buffer A (35 mM Tris-HCl (pH 7.5), 25 mM KCl, 10 mM MgCl2, 250 mM sucrose). The bacteriocytes were crushed by pipetting and subjected to filtration through a 5-µm filter to obtain Buchnera.

We prepared genomic DNA from Buchnera cells by a standard phenol/chloroform protocol. The shotgun sequence libraries were prepared as described24, except that we used vectors with cohesive ends (one with a T-overhang and one partially filled) to avoid chimaera formation. Briefly, the genomic DNA fragments were hydrodynamically sheared using HydroShear (GeneMachines), blunt-ended and subjected to A-tailing. The A-tailed fragments were ligated with pGEM-T Easy vector (Promega). The method of using partially filled-in restriction endonuclease fragments has been described25. The sequences were assembled using PHRED (P. Green and B. Ewing, University of Washington) and PHRAP (P. Green, University of Washington) and the consensus sequence was checked and edited using CONSED (D. Gordon, University of Washington). The gaps between the contigs were closed by primer walking. About 7-fold genome coverage was achieved by 9,747 sequencing reactions. According to CONSED, the overall error probability was estimated at less than 0.01%. The sizes of the predicted restriction endonuclease fragments coincided with the physical map5.

Informatics

We used two strategies for identifying ORFs. An initial set of ORFs likely to encode proteins was identified by the GeneHacker program, a system for gene structure prediction using a hidden Markov model (HMM)26. Both predicted ORFs and the intergenic regions were compared against a non-redundant protein database using the BLAST (S. F. Altschul, et al., NCBI) programs. Combining these results, we identified and annotated the ORFs. Frameshifts were detected and corrected where appropriate as described27. The isoelectric point for each protein was predicted using the ISOELECTRIC program in the GCG analysis suite (Genetics Computer Group). Possible metabolic pathways were examined using the online service KEGG28.

Comparative genomic analysis was performed, using 23 complete prokaryotic genomes: Haemophilus influenzae (NC_000907), Mycoplasma genitalium (NC_000908), Methanococcus jannaschii (NC_000909), Synechocystis sp. (NC_000911), Mycoplasma pneumoniae (NC_000912), Helicobacter pylori 26695 (NC_000915), Helicobacter pylori J99 (NC_000921) , Escherichia coli (NC_000913), Methanobacterium thermoautotrophicum (NC_000916), Bacillus subtilis (NC_000964), Archaeoglobus fulgidus (NC_000917), Borrelia burgdorferi (NC_001318), Aquifex aeolicus (NC_000918), Pyrococcus horikoshii (NC_000961), Pyrococcus abyssi (NC_000868), Mycobacterium tuberculosis (NC_000962), Treponema pallidum (NC_000919), Chlamydia trachomatis (NC_000117) , Rickettsia prowazekii (NC_000963), Chlamydia pneumoniae (NC_000922) , Aeropyrum pernix (NC_000854), Thermotoga maritima (NC_000853) and Buchnera sp. APS. See Supplementary Information. These sequence data, except the Buchnera genome, were obtained from Entrez Genomes at NCBI website (http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/entrez/query.fcgi?db = Genome).

Paralogue and orthologue analyses were performed on the amino-acid sequences of all the predicted genes based on the BLAST bit scores. Species-specific duplicated genes were defined as paralogues of the same species that were more similar to each other than to any genes of other species. Orthologue groups were determined using an orthologue identification method29, by taking into account gene duplications after speciation and multi-domain structures. For each orthologue group, the following analyses were carried out with our original script package, Whole genome Analysis Tools (WAT), for automated phylogenetic analyses: multiple alignment construction with CLUSTALW (J. Thompson et al.. EMBL), extraction of conserved regions, using a program, xcons (H. W., unpublished), calculation of the distances between the group members with the PROTDIST program of the PHYLIP program package (J. Felsenstein, University of Washington), and construction of a neighbour-joining tree. Conserved regions were defined as the common segments in the CLUSTALW alignment, all possible pairs of which should show positive alignment scores using a local alignment scoring method.

The gene set in the LCA was inferred by a simple cladistical methodology. For a given tree topology, the gene set in the LCA of a clade is inferred from the assumption that the LCA had an ancestral gene for each orthologue group identified between the sister groups of the LCA or between descendant of the LCA and outgroup of the clade radiating from the LCA. This is a reasonable assumption as orthologous genes are defined as descendants of a single ancestral gene in the LCA inherited by different species, and an ancestral species should have had an ancestral orthologue corresponding to an orthologue pair identified between the descendant and the ancestor/outgroup. The actual gene set of the LCA may be larger than the one inferred as some genes could have been lost or evolved rapidly in either or both of the sister groups. The gene list of the LCA of Buchnera, E.coli, and H. influenzae, and the information on the WAT scripts used for this LCA analysis is available on request.

References

Munson, M. A., Baumann, P. & Kinsey, M. G. Buchnera, new genus and Buchnera aphidicola , new species, a taxon consisting of the mycetocyte-associated, primary endosymbionts of aphids. Int. J. Syst. Bacteriol. 41 , 566–568 (1991).

Ishikawa, H. Biochemical and molecular aspects of endosymbiosis in insects. Int. Rev. Cytol. 116, 1–45 (1989).

Baumann, P., Moran, N. A. & Baumann, L. in The Prokaryotes (ed. Dworkin, M.) (Springer, New York, 2000).

Komaki, K. & Ishikawa, H. Intracellular bacterial symbionts of aphids possess many genomic copies per bacterium. J. Mol. Evol. 48, 717–722 ( 1999).

Charles, H. & Ishikawa, H. Physical and genetic map of the genome of Buchnera, the primary endosymbiont of the pea aphid Acyrthosiphon pisum. J. Mol. Evol. 48 142– 150 (1999).

Buchner, P. Endosymbiosis of Animals with Plant Microorganisms (Wiley, New York, 1965).

Moran, N. A., Munson, M. A., Baumann, P. & Ishikawa, H. A molecular clock in endosymbiotic bacteria is calibrated using the insect hosts. Proc. R. Soc. Lond. B 253, 167– 171 (1993).

Fraser, C. M. et al. The minimal gene complement of Mycoplasma genitalium. Science 270, 397–403 (1995).

van Ham, R. C., Moya, A. & Latorre, A. Putative evolutionary origin of plasmids carrying the genes involved in leucine biosynthesis in Buchnera aphidicola (endosymbiont of aphids). J. Bacteriol. 179, 4768– 4777 (1997).

Douglas, A. E. Nutritional interactions in insect-microbial symbioses: aphids and their symbiotic bacteria Buchnera. Annu. Rev. Entomol. 43, 17–37 (1998).

Moran, N. A. Accelerated evolution and Muller's rachet in endosymbiotic bacteria. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 93, 2873– 2878 (1996).

Houk, E. J. & Griffiths, G. W. Intracellular symbiotes of the Homopltera. Annu. Rev. Entomol. 25, 161–187 (1980).

Sasaki, T. & Ishikawa, H. Production of essential amino acids from glutamate by mycetocyte symbionts of the pea aphid, Acyrthosiphon pisum. J. Insect. Physiol. 41, 41– 46 (1995).

Nakabachi, A. & Ishikawa, H. Provision of riboflavin to the host aphid, Acyrothosiphon pisum, by endosymbiotic bacteria, Buchnera . J. Insect. Physiol. 45, 1– 6 (1999).

Mittler, T. E. Dietary amino acid requirements of Aphid Myzus persicae affected by antibiotic uptake. J. Nutr. 101, 1023 –1028 (1971).

Whitehead, L. F. & Douglas, A. E. A metabolic study of Buchnera, the intracellular bacterial symbionts of the pea aphid Acyrthosiphon pisum. J. Gen. Microbiol. 139, 821–826 (1993).

Douglas, A. E. Sulphate utilization in an aphid symbiosis. Insect. Biochem. Mol. Biol. 18, 599-605 (1988).

Tomii, K. & Kanehisa, M. A comparative analysis of ABC transporters in complete microbial genomes. Genome Res. 8, 1048–1059 (1998).

Kubori, T. et al. Supramolecular structure of the Salmonella typhimurium type III protein secretion system. Science 280 , 602–605 (1998).

Young, G. M., Schmiel, D. H. & Miller, V. L. A new pathway for the secretion of virulence factors by bacteria: the flagellar export apparatus functions as a protein-secretion system. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 96, 6456 –6461 (1999).

Marais, A., Bove, J. M. & Renaudin, J. Characterization of the recA gene regions of Spiroplasma citri and Spiroplasma melliferum. J. Bacteriol. 178, 7003–7009 ( 1996).

Eisen, J. A. & Hanawalt, P. C. A phylogenomic study of DNA repair genes, proteins, and processes. Mutat. Res. 435, 171–213 (1999).

Nogueira, T. & Springer, M. Post-transcriptional control by global regulators of gene expression in bacteria. Curr. Opin. Microbiol. 3, 154–158 ( 2000).

Fleischmann, R. D. et al. Whole-genome random sequencing and assembly of Haemophilus influenzae Rd. Science 269, 496– 512 (1995).

Hattori, M. et al. A novel method for making nested deletions and its application for sequencing of a 300 kb region of human APP locus. Nucleic Acids Res. 25, 1802–1808 ( 1997).

Yada, T. & Hirosawa, M. Detection of short protein coding regions within the cyanobacterium genome: application of the hidden Markov model. DNA Res. 3, 355– 361 (1996).

Tomb, J. F. et al. The complete genome sequence of the gastric pathogen Helicobacter pylori. Nature 388, 539– 547 (1997).

Ogata, H. et al. KEGG: Kyoto Encyclopedia of Genes and Genomes. Nucleic Acids Res. 27, 29–34 ( 1999).

Watanabe, H., Mori, H., Itoh, T. & Gojobori, T. Genome plasticity as a paradigm of eubacteria evolution. J. Mol. Evol. 44 (Suppl. 1), S57–S64 ( 1997).

Riley, M. Functions of the gene products of Escherichia coli. Microbiol. Rev. 57, 862–952 ( 1993).

Acknowledgements

We thank the technical staff of RIKEN GSC, M. Horishima, H. Ishizaki, N. Ota and Y. Seki for sequencing; T. Yada for ORF prediction; A. Toyoda for technical support on the sequence library preparation; C. Kawagoe for computer system support; and T. D. Taylor for discussion. This work was supported by a grant from the Program for Promotion of Basic Research Activities for Innovation Biosciences (ProBRAIN) of the Bio-oriented Technology Research Advancement Institution, and Grants-in-Aid for Scientific Research from the Japanese Ministry of Education, Science, Sports and Culture.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Supplementary information

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Shigenobu, S., Watanabe, H., Hattori, M. et al. Genome sequence of the endocellular bacterial symbiont of aphids Buchnera sp. APS. Nature 407, 81–86 (2000). https://doi.org/10.1038/35024074

Received:

Accepted:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/35024074

This article is cited by

-

In vivo interference of pea aphid endosymbiont Buchnera groEL gene by synthetic peptide nucleic acids

Scientific Reports (2024)

-

Root aphid (Aploneura lentisci) population size on perennial ryegrass is determined by drought and endophyte strain

Journal of Pest Science (2024)

-

Coordination of host and endosymbiont gene expression governs endosymbiont growth and elimination in the cereal weevil Sitophilus spp.

Microbiome (2023)

-

Physiological and evolutionary contexts of a new symbiotic species from the nitrogen-recycling gut community of turtle ants

The ISME Journal (2023)

-

Comparative transcriptomics of aphid species that diverged > 22 MYA reveals genes that are important for the maintenance of their symbiosis

Scientific Reports (2023)

Comments

By submitting a comment you agree to abide by our Terms and Community Guidelines. If you find something abusive or that does not comply with our terms or guidelines please flag it as inappropriate.